Remembering The Mekhitarists /

Mekhitarian Order after 50 years

The Mekhitarist Monastery is located in the heart of Vienna, Austria,

on a street named after it.

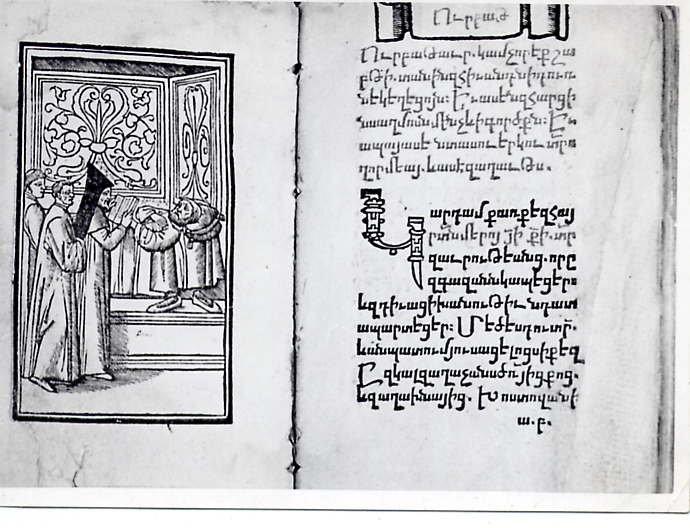

Photostat of the first Armenian book printed in

Venice in 1512 by Hagop Meghabart. Take note of the striking artwork which

accompanies the text.

It is here where a cadre of Armenian Catholic Fathers has gathered since the

late 18th century to preserve Armenian culture and literature, preach

to the faithful, heighten the spiritual and intellectual development of the

Armenian people, and educate its youth.

It is here that a prominent religious order has contributed greatly toward

bringing Armenians to the forefront of European thought through publications in

Latin, French, German, Italian, and English.

It is here where Armenians famous and not-so-famous visit from around the

world to satisfy their inhibitions, see antiquity in progress, peruse through an

enormous library of books and coins, marvel over some of the greatest artwork

ever presented, and tour an imposing “garden of paradise” with rich

horticultural blessings.

It is here where I had the privilege of spending a year’s time while still a

teenager looking for adventure. A freshman at Boston University at the time, I

was at the crossroads of indecision. I had already changed my major once from

chemistry to accounting, and was failing miserably.

Things weren’t going particularly well on the home front. I had broken off

with a girlfriend, and could no longer tolerate my father’s luncheonette

business after being weaned in it.

To put it bluntly, I needed a change in my life. It came one Sunday shortly

before Christmas after serving Mass as a deacon at Holy Cross Armenian Catholic

Church in Harvard Square.

Father Luke Arakelian, pastor at the time, came up with a proposal that got

me thinking. He offered to send me to Vienna in a pilot program to study

Armenian language and religion with the priests. Not to be ordained as one,

simply to enhance my skills.

It would mean a year’s hiatus from college. Two other youth were also tapped

for the venture, me being the older one. If it worked, others would follow from

America.

Recognizing the urgent need of propagating Armenian heritage among our youth,

a program of Armenian education was launched in America during that year in

1960. Essentially, we would be trailblazers inside a monastic environment few

our age had ever ventured for any length of time.

Thus began an experience of a lifetime that introduced me to a heritage I

never quite appreciated, gave me an introduction to journalism that turned into

a career, and enamored me into a world of spirituality that provided a better

appreciation for God and my church.

The most difficult part of the invitation was selling it to my parents.

Father Luke left that to me.

“What, you’re going to a monastery and becoming a priest?” my mother groaned.

“Catholic priests are celibate. They don’t marry. Does this mean I won’t see any

grandchildren?”

My father was less emphatic. He was more concerned about the business and

sudden shortage of help, not to mention the interruption of college studies. My

mind was set. I was prepared to embark to a country I had never seen with two

other boys I hardly knew, both of whom would be taking a year off from high

school.

My professors wished me well. So did my friends and fellow AYFers. I had just

joined the Somerville Chapter. James Tashjian, the editor of the Hairenik

Weekly, took me aside with a request. He asked for a series of articles that

would shed light on the religious order.

We had met through occasional AYF reports I had sent him. This would become

an assignment of a lifetime—one that would provide an insatiable thirst for

journalism. Would these priests even want to share their personal lives with the

outside world? Who was I to suddenly barge into their home and exploit them?

The first entry in my journal came from Father Luke. It read: “Dear Thomas. I

wish you the best and God’s blessings upon this educational experience. Your

conduct in Vienna is most important. The impression you, Kenny [Maloomian], and

Aram [Karibian] make with the Mekhitarist Fathers will decide upon the future of

this program. Hopefully, others will follow you to this sacred ground.”

To let Father Luke down would have been a travesty. For seven years, I had

served him faithfully each Sunday on the altar, accompanied him on trips, owed

my self-esteem and integrity to the beloved cleric, and regarded him as a second

“father” in my life.

With my faith teetering, my senses unraveled, off I headed toward Vienna—the

city of Strauss, Mozart, and a coterie of priests awaiting my arrival.

My arrival at the Vienna Mekhitarist Monastery in 1960 was met by Archbishop

Mesrop Habozian, the abbot general of the order.

Vienna Mekhitarist Order, as it appeared in 1960. In

rear are American students Aram Karibian, Tom Vartabedian and kenneth Maloomian.

His intimidating presence before me with a long, white flowing beard and

large cross hanging over his chest left an immediate impression.

The introduction was erroneous. He asked if I needed anything and I answered

him in broken Turkish Armenian, to which he made an oral correction. I needed a

shave.

From that day on, I began every morning with altar duty, serving Mass for the

archbishop with my deacon’s robe and attempting to converse intelligently in

Armenian. He acted as my instructor.

When he walked into the dining room, his entourage would stand in prayer. I

later found out he had been a teacher in his priestly days and managed the

printing shop at the vank (monastery) prior to his elevation. The

twinkle in his eye remained constant and his sense of humor indeed admired.

I remember once being admonished for keeping late hours outside the big

house, and even once defying a curfew. His angst was short-lived and he treated

me to an unforgettable experience.

I accompanied the archbishop to the Vienna Opera House where I got to meet

the great Soviet Armenian composer Aram Khachaturian. We enjoyed his “Gayane

Suite” that evening and engaged in conversation later. As memory would have it,

he found my visit with the Fathers an invaluable exercise toward the future

welfare of youth in this country.

The next day, we met once again inside the monastery where Khachaturian saw

the priests and wished them well in their work. In the months that followed,

many famous Armenians walked through the doors.

One moment it was William Saroyan, the next George Mardikian, author of

Song of America and the inspiration behind ANCHA, not to mention his

popular restaurant Omar Khayyam in California, a popular haven for

discriminating diners.

I wore a number of hats inside the monastery. In addition to my daily service

at Mass, I would assist in the distillery, which produced the finest liqueurs in

Europe, and lend a hand in the library, which contained over 170,000 books.

Fifty of them were written by Father Nerses Akinian, an incredible scholar,

who served as librarian at the venerable age of 78. No doubt, one of the most

learned and astute Armenian scholars in the world. We got along just fine with

mutual admiration. He called me Tovmas.

Also contained in the library was a rare coin collection totaling some 4,000

pieces, under glass, dating from Dikran the Great (60 BC) to King Levon V

(1375).Complementing the collections were an incredible art display featuring

work from the famous Naghash family artists from the 18th century and

Ayvazovsky with his oceanic scenes

Being in such erudite company, I suppose, made an impression upon this

19-year-old.

But don’t get the idea this was some joyride. My classes each day were

mandatory, answering to Brother Vartan Ashkarian, a no-nonsense type, who

imposed excellence upon his students. One mishap and you were grounded the next

day.

Classes would run from 10 to noon, and 1-3. We were allowed to roam outside

the grounds until 5 when the dinner bell sounded. From 6-8, we would gather with

the priests, play tavlou, listen to the radio (no television), and

engage in conversation.

From there, it was off to my room for homework and up at 6 the next morning

to serve Mass for the archbishop. The routine seldom changed. On Sundays, a

choir composed of Austrians would flock into church and sing the Badarak.

The voices were impeccable.

That year in 1960, I had the pleasure of being surrounded by 15 priests and 3

older seminarians on the verge of being ordained. A short distance away was a

village that housed younger seminarians attending school. Some would accept

their vows. Most were there just for the education.

Each priest was an entity unto its own and I often wondered how a group of

men, personalities diverse, could bond the way they did. And how, despite some

advanced ages, they could maintain such a diligent literary pace.

Members bound themselves to four simple but permanent vows: obedience,

chastity, poverty, and missionary work. The Mekhitarists have perfectly

understood that good reading raises and educates, while bad reading lowers and

destroys the soul.

A multi-lingual printing press was working overtime, including a periodical

called “Handes Amsora,” which was circulated internationally to critical

acclaim.

I had enough to do just getting through a simple Armenian grammar and making

myself sound intelligent.

Living inside a monastery for the better part of a year with no dating

privileges and no television was certainly sacrificial on my part and those

around me.

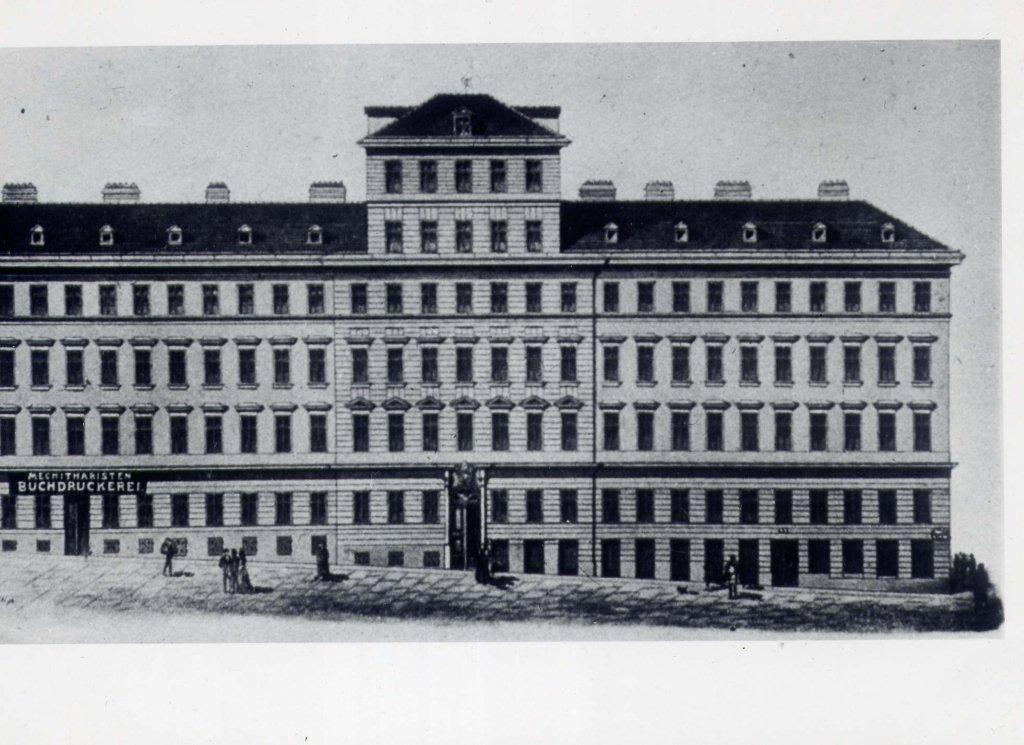

The Motherhouse of the Mekhitarist Congregation in

Vienna has been the center of Armenian culture and education in Austria since

1810.

As a 19-year-old, I had just finished a year at Boston University, helped

reorganize the Armenian Club there, and beefed up the membership by inviting

Harvard-Radcliffe and Tufts students to join the ranks. Life was good.

The social calendar was brisk. We had begun to make an impact on campus and

here I was, behind monastery walls with a religious order, many of them old

enough to be my grandfather. Although the Mekhitarist Fathers were

multi-lingual, English was not one of their primary languages.

I could either learn German or brush up on my Armenian, which is why I was

there in the first place. Being immersed made it relatively easy. Both languages

were exercised inside the monastery.

There were moments when you could slide into tedium, but for the most part,

you created your own environment. Vienna was a marvelous city. On many an

occasion, I had a front-row seat at St. Stephen’s Cathedral, listening to the

Vienna Boys’ Choir.

Being introduced to the world-famous Lipizzaner horses was yet another

revelation. The many parks and fountains made an afternoon stroll all the more

exhilarating. On several occasions, a weekend was spent in the Vienna woods and

by the Danube with a priest or two. Leg power was the mode.

More than once, I paid a visit to Mozart’s grave and encountered other

classical music buffs who cherished his many compositions. From loud speakers

nestled in the ground came everything from his “Clarinet Concerto” to his “Don

Giovanni Suite.”

Any apprehensions I had at being away from home and settled into an austere

zone had quickly evaporated. The Fathers were amicable, pleasant, very ordinary,

and entertaining. They did not appear to be among the world’s greatest scholars

and historians.

Letters arrived from home with consistency. I opened one envelope and out

sifted beach sand with a note: “See what you’re missing back home.”

I wrote back in Armenian. “See what you’re missing by not being here.” The

intent was well taken.

Some of the best Armenian food I ever tasted was served inside the vank,

diligently prepared by Austrian cooks. Sunday dinners were special and served

with wine and beer. Given our age, we refrained from indulging.

An old piano was given a new lease on life by Father Gregory Heboyan, who

played Armenian selections like a virtuoso, especially his version of “Sabre

Dance.”

Most every priest had a specific talent that was exercised. Some of the best

tavlou and chess games were instituted here and rivalries were usually

heightened.

I had never been introduced to Raffi as a writer until I picked up a copy of

his book The Fool, translated into English. I found the work a

delightful read and wound up naming a son after him.

While I am no Bibliophile, I did appreciate the volume and capacity with

which these Fathers worked behind closed doors, spilling out works like a

veritable publishing house.

They sustained themselves with meager sales. Their thirst for knowledge was

self-ingrained, prompted only by their enthusiasm to remain private. Perhaps

that is why I found their company rather insightful.

Throughout the diaspora, Mekhitarist schools and mission houses developed

aptitude and gave many a student the opportunity to advance with special

emphasis on patriotism and religion.

In the years that followed, it was this education that advanced my ability to

teach Armenian, serve my Christian faith, and remain loyal to the cause of

humanity. Truth be told, had my parents not intervened, I may have joined the

clergy, living up to my surname.

Now, five decades later, I never did get back to visit, much as I had wished,

but I did communicate. Every Christmas, gifts were sent to the young

seminarians. My instructor went on to become a leader of the Order. Another

proceeded to become abbot general of the Motherhouse. Our paths have since

crossed in a welcoming embrace.

A decade ago saw the unification of both monasteries (Vienna and Venice) as

the Order continues to endure like the rock of ages. We owe it to ourselves as

Armenians to pay homage, regardless of denomination.

Protestant. Catholic. Apostolic. We’re all birds of the same flock. Think of

the inevitable. Had there not been a Mekhitarist Order, our literary

contributions would not have flourished and guys like myself may have gone

astray.

You and I owe them a debt of allegiance.

|